Can I lose money by getting a pay increase? Could my taxes go up higher than my pay increase if it bumps me into a higher tax bracket?

There is a common myth that someone can actually lose money by accepting a raise if it pushes them into a higher tax bracket. The story usually suggests that someone could be making, for example, $49,000 at a 30% tax rate. Then they accept a raise that bumps them up to $51,000 where they’d get taxed at 35% and, boom!, they’re suddenly taking home less money.

Before the raise the person is making $49k, minus the taxes ($49k * 30%). This leaves them with $49,000 – 14,700 = $34,300 to take home. After the raise they’d be making $51k, minus the taxes ($51k * 35%). After the raise the employee ends up with $51,000 – $17,850 = 33,150. In other words, it looks like taking the raise results in the employee making $1,150 less than before!

At first glance, the idea of accepting a small raise and getting bumped into a higher tax bracket, resulting in lower pay seems to make sense. However, it overlooks how our tax system actually works.

Our money is not taxed at a flat rate. In other words, if you’re in the “over $50k” tax bracket, not all of your money is taxed at the 35% rate. What actually happens is all the money you make up to a certain point is taxed at the lower rate (30% in the above example). Then any money you make beyond that is taxed separately in the higher bracket.

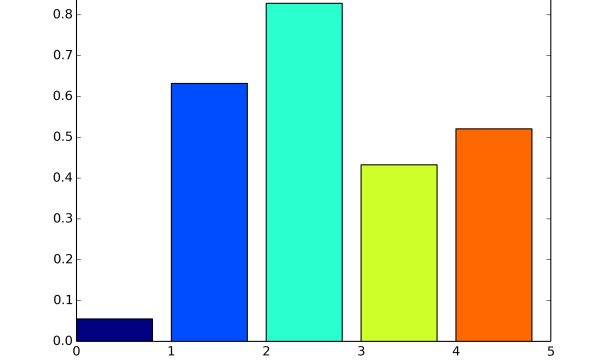

Let’s look at the above example again, this time considering how money earned in different brackets is taxed at different rates. Before the employee gets their raise they were making $49k and taxed at 30%. This gave them $34,300 to take home.

Now, if they accept a raise and start making $51,000 what will happen? They will be taxed 30% on the first $50,000 ($15,000 will be taken off their pay). Then they will be taxed 35% on the remaining $1,000 (the amount remaining above the 50k mark). This means the lower bracket is taxed $15,000 and the $1,000 in the higher bracket is taxed $350, for a total of $15,350. Their total take home pay is $51,000 – $15,350 = $35,650. The employee ends up taking home $1,350 more than they did prior to their raise. In other words, even once the employee is pushed into the higher tax bracket, their $2,000 raise still nets them an extra $1,350 in take home money.

The idea of “more money means more taxes, resulting in lower pay” is a common myth. I suspect it continues to spread because the fiction (a flat tax rate for all your income) seems to make more sense and is easier to picture than the reality, which is a incremental set of separate tax brackets.

It is also true that sometimes when a person gets a raise it is also at a time when their CPP/EI contributions are being reset and those might be temporarily higher than usual. This often leads to people receiving their first paycheque of the year (or of a quarter) and discovering they took home less money, despite receiving a raise. The raise isn’t what caused their deductions to go up, resulting in less money. It’s just a coincidence their CPP and EI deductions are resetting at the same time as their raise taking effect. But it creates an illusion that their raise resulted in less take home money and perpetuates the myth of raises robbing people of their net income.

Under any normal circumstances, a raise in pay will not result in a lower amount of money being taken home. Even if you’re bumped into a higher tax bracket, only the money you receive in the higher bracket is taxed at the higher amount. The money you made below the new bracket is still taxed at the lower rate. This means you end up taking home more money.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.